Pisa, Palazzo Toscanelli Lanfranchi

Introduction

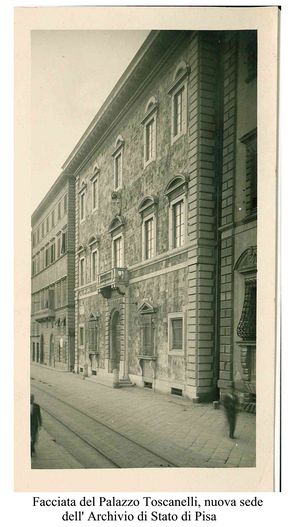

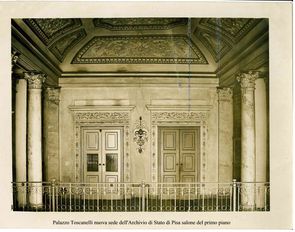

The Palazzo Toscanelli Lanfranchi [Fig. 1], today home to the State Archives of Pisa, was the residence chosen by Lord Byron during his stay in the city. It was Percy Bysshe Shelley who recommended it to him, calling it “the finest palace on the Lung’Arno” for his friend in a letter to Leigh Hunt, in which the project The Liberal is mentioned for the first time. Byron arrived in Pisa in November 1821, accompanied by Teresa Guiccioli and her father and brothers, the Counts Gamba. While the poet took up residence at Palazzo Lanfranchi [Fig. 2], the Gambas initially settled in the nearby Palazzo Finocchietti (now Palazzo Medici) and later in Casa Parra (now part of the Hotel Nettuno complex).

Byron’s arrival, along with his entourage, caused some unease among the local authorities, who requested guidance from the regional government on how to proceed. They were advised to exercise the utmost discretion: the poet and the Gambas were granted full freedom of movement, although their activities were still monitored by the pro-Austrian police.

Byron, however, did little to remain inconspicuous. According to Thomas Medwin, his entry into Pisa was decidedly “in style”: the poet arrived with “seven servants, five carriages, nine horses, a monkey, a bull-dog and a mastiff, two cats, three pea-fowls and some hens.” Byron’s impression of the palace was extremely favourable, and he repeatedly expressed his enthusiasm for his new lodgings, which seemed perfectly suited to his taste for Gothic atmosphere [Fig. 3] and to the romantic vision of Italy – particularly its medieval towns – that fascinated him so deeply.

In July 1822, Leigh Hunt also arrived in Pisa with his large family, joining the so-called “Pisan Circle.” They were hosted by Byron at Palazzo Lanfranchi, considered spacious enough to accommodate them all, although Hunt’s mood upon arrival does not seem to have been very cheerful, as he mentions in a letter to Thomas Moore.

Despite these challenges, the Pisan stay was a period of intense creative activity. Byron continued working on Don Juan, composing Cantos VI–IX, and with Leigh Hunt’s presence, the editorial project The Liberal finally took shape. Byron contributed to the first volume of this initiative with the satirical poem The Vision of Judgement, written in response to Robert Southey and consistent with the overarching aim of The Liberal: to offer a critical perspective on British culture and politics as observed from southern Europe.

Palazzo Lanfranchi was also the scene of one of the most dramatic episodes of Byron’s Pisan stay, which ultimately forced him to leave the city for Livorno: the wounding of Sergeant Major Masi. Returning hurriedly to Pisa after leaving for lunch, eager to arrive in time for the military review, Masi collided abruptly with a group of Englishmen, including Byron, the Shelleys, Countess Guiccioli, Captain Hay (an old acquaintance of the poet), and the Irishman John Taaffe.

The incident sparked a violent altercation that quickly escalated: Captain Hay was injured in the nose, while Shelley was struck on the head and unhorsed. Upon returning to Pisa, Masi was pursued by Byron, who demanded satisfaction for the affront to the group; the two agreed to a formal duel the following day, in accordance with contemporary custom. The confrontation, however, ended far more gravely in front of Palazzo Lanfranchi, where the sergeant major was nearly fatally wounded by one of Byron’s servants.

The episode led to a legal case, giving local authorities a pretext to reinforce their suspicions about the poet and his entourage, portraying Byron (and especially the Gambas) as potentially dangerous and subversive figures.

Today, Palazzo Toscanelli (formerly Lanfranchi) houses a 19th-century fresco by Nicola Cianfanelli [Fig. 4], known as Byron and Poetry, located in the current Inventory Room of the State Archives (which probably corresponded to Byron’s chamber) and dedicated to the poet immersed in the act of creation, symbolizing the bond between Italy and the English Romantic spirit.

Documents

- To Leigh Hunt. Pisa, 26th August, 1821. (SHELLEY, Percy Bysshe (1964). The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, ed. F. L. Jones, 2 vols, Oxford, Clarendon Press)

My dearest Friend,

Since I last wrote to you, I have been on a visit to Lord Byron at Ravenna. The result of this visit was a determination on his part to come and live at Pisa; and I have taken the finest palace on the Lung’ Arno for him. But the material part of my visit consists in a message which he desires me to give you, and which I think ought to add to your determination, for such a one I hope you have formed, of restoring your shattered health and spirits by a migration to these “ regions mild of calm and serene air.” He proposes that you should come and go shares with him and me in a periodical work, to be conducted here; in which each of the contracting parties should publish all their original compositions, and share the profits. (908-909)

- Thomas Medwin, Medwin’s Conversations of Lord Byron. ([1966)] .ed. Ernest J. Lovell, Jr., Princeton, Princeton University Press)

20th November.

“This is the Lung’ Arno. He has hired the Lanfranchi palace for a year: – it is one of those marble piles that seem built for eternity, whilst the family whose name it bears no longer exists,” said Shelley, as we entered a hall that seemed built for giants. “I remember the lines in the ‘Inferno,’” said I: “a Lanfranchi was one of the persecutors of Ugolino.” – “The same,” answered Shelley; “you will see a picture of Ugolino and his sons in his room.” Fletcher, his valet, is as superstitious as his master, and says the house is haunted, so that he cannot sleep for rumbling noises overhead, which he compares to the rolling of bowls. No wonder; old Lanfranchi’s ghost is unquiet, and walks at night.” (4)

His travelling equipage was rather a singular one, and afforded a strange catalogue for the Dogana: seven servants, five carriages, nine horses, a monkey, a bull-dog and a mastiff, two cats, three pea-fowls and some hens, (I do not know whether I have classed them in order of rank,) formed part of his live stock; and all his books, consisting of a very large library of modern works, (for he bought all the best that came out,) together with a vast quantity of furniture, might well be termed, with Caesar, “impediments.” (3)

- To Thomas Moore, Pisa, July 12th, 1822 (BYRON, George Gordon, Lord (1973-94). Lord Byron’s Letters and Journals, ed. Leslie A. Marchand, 13 vols, Vol. 9, London, John Murray)

Leigh Hunt is here, after a voyage of eight months, during which he has, I presume, made the Periplus of Hanno the Carthaginian, and with much the same speed. He is setting up a Journal, to which I have promised to contribute; and in the first number the “Vision of Judgement, by Quevedo Redivivus,”’ will probably appear, with other articles. Can you give us any thing? He seems sanguine about the matter, but (entre nous) I am not. I do not, however, like to put him out of spirits by saying so; for he is bilious and unwell. Do, pray, answer this letter immediately. Do send Hunt any thing in prose or verse of yours, to start him handsomely – any lyrical, irical, or what you please. (183)

Texts

The drying up a single tear has more

Of honest fame, than shedding seas of gore.

Alas! it is not so. Who would not rather

Have fame for killing, than for saving lives?

The pageant of the day goes on; the father

Of all the hero’s virtues – enterprise –

Is but a youthful ferocity;

And those who call it courage, are too wise

To speak of it as violence: the rest

Is mere parade, and patriotism’s dress.

Images

Bibliography

Byron, George Gordon, Lord Lord Byron’s Letters and Journals, ed. Leslie A. Marchand, 13 vols, Vol. 9, London, John Murray,1973-94.

Byron, George Gordon, Lord, The Complete Poetical Works of Lord Byron, edited by Jerome J. McGann and Barry Weller, 13 vols, Oxford University Press (Clarendon Press), 1980–93.

Curreli, Mario, Scrittori inglesi a Pisa: viaggi, sogni, visioni dal Trecento al Duemila, Pisa, ETS, 2005.

Medwin, Thomas, Medwin’s Conversations of Lord Byron, ed. Ernest J. Lovell, Jr., Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1966.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe, The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, ed. F. L. Jones, 2 vols, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1964.

Villani, Stefano, “l Grand Tour degli inglesi a Pisa (secoli XVII-XIX)”, in E. Daniele (ed.), Le dimore di Pisa. L’arte di abitare i palazzi di una antica Repubblica Marinara dal Medioevo all’Unità d’Italia, Atti del Convegno di studi, Firenze, Alinea, 2010, pp.173-180.

Ultimo aggiornamento

19.02.2026