The Pisan Salons and Literary Academies in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Nicoletta Caputo (University of Pisa)

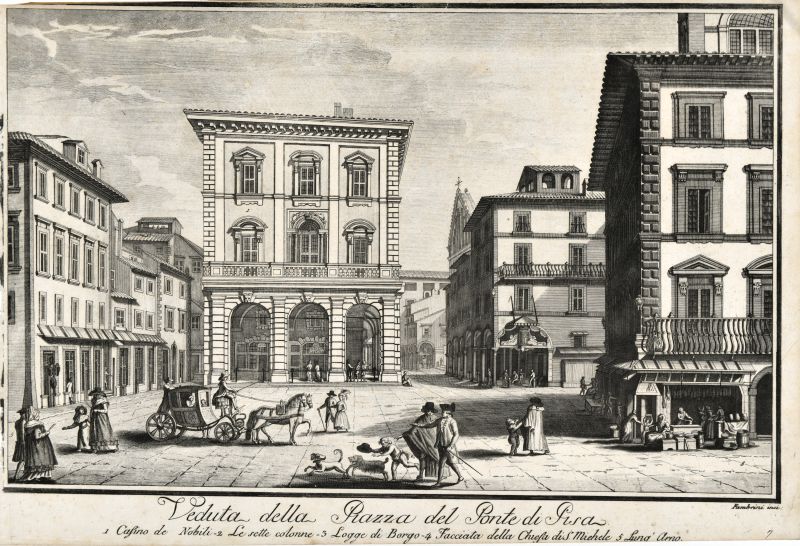

Although in her comment to Percy’s 1820 poems Mary described Pisa as a “quiet half-unpeopled town” (M. Shelley 1839, p. 279), when, in January 1820, the Shelleys settled in the city, it already could vaunt a long tradition of hospitality, as witnessed by the Casino dei Nobili (Panajia 1996, pp. 209-13), whose foundation had been decreed by the Pisan aristocracy precisely to offer “in the wake of the custom of the Sienese and Florentine nobility […] suitable premises for collective use, for the fulfillment of social obligations towards passing travellers or foreign residents ‘of distinction’” (Panajia 2021, p. 41). Pisa was mainly chosen as a travel destination and as a residence for “the extreme mildness of the climate” (M. Shelley 1839, p. 279) and for the presence of the Baths of San Giuliano nearby, which had been restored starting in 1742 and attracted the best European aristocracy (Salvetti 1993, p. 6). The Casino dei Nobili opened in 1754, and the new Ballroom was inaugurated in 1788 (Salvetti 1993, pp. 15-20). The Casino dei Nobili was also attended by members of the grand ducal family, who usually spent the winter in Pisa, where the climate was milder than in Florence.

Ferdinando Fambrini, the Casino dei Nobili in the second half of the 18th century ( CC BY 4.0)

Pisa, however, did not only attract aristocrats, but also illustrious literati, who preferably rented houses on the Lungarni (like the Shelleys and Lord Byron did) and frequented the Pisan salons and literary academies. In the mid-18th century, Carlo Goldoni came, who remained in the city from September 1744 to April 1748, working as a lawyer (De Fecondo and Timpanaro 2010). In Pisa, Goldoni was welcomed by the men of letters associated with the “Colonia Alfea” of the “Accademia dell’Arcadia” (or “Accademia degli Arcadi”), which he joined under the name of Polisseno Fegejo (Curreli 2000, p. 26). The “Alfea Colony” of the “Academy of Arcadia” had been founded in 1700 and was one of the twenty-five academies that flourished in Pisa during the 17th and 18th centuries (Agostini and Scarselli 2024). Goldoni was probably also in contact with the circles of Freemasonry.

Vittorio Alfieri followed, who first came to Pisa in 1776. On this occasion, he only stayed “six or seven weeks” (Alfieri 1983, p. 181), but he still had time to get to know “all the most illustrious professors” (Alfieri 1983, p. 181) at the local university, including Francesco Vaccà Berlinghieri, father to Leopoldo and Andrea Vaccà Berlinghieri. He was again in Pisa eight years later. This time, he remained in the city from November 1784 to September 1785, lodging in Via Santa Maria 36 (at Palazzo Nervi, now Palazzo Venera), and he employed as his secretary Gaetano Polidori, father to John William Polidori (Lord Byron’s physician and author of The Vampyre) and grandfather to Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Most interesting, however, is Alfieri’s final visit to Pisa, which was also the shortest. He came on 16 June 1795 for the patronal feast of San Ranieri to see the “luminara”, which he had so appreciated ten years earlier, and played the title role in his tragedy Saul. The play was staged by a company of young amateur actors at the small theatre in Palazzo Roncioni, on the Lungarno. He was invited to take part in this performance by Count Angiolo Roncioni, who had created a cultural circle called the “Roncioni Academy”. As Alfieri wrote in his memoirs, “and there being in Pisa in the private house of some Lords another company of amateurs, who also performed Saul, I, invited by them to go there for the ‘luminara’, had the childish vainglory to go, and I performed only once, and for the last time, my beloved part of Saul; and there I remained, as far as the theatre is concerned, dead as a king” (Alfieri 1983, p. 269).

Count Angiolo Roncioni’s daughter, Isabella, was intensely loved by Ugo Foscolo and inspired the character of Teresa in his epistolary novel Le ultime lettere di Jacopo Ortis (Last letters of Jacopo Ortis), published in 1802, while Palazzo Roncioni was the home of Mme De Staël when, between 1815 and 1816, she spent several months in Pisa with her second husband, the young Swiss officer Jean de Rocca. At Palazzo Roncioni, the wedding between her daughter Albertine and the Duke Vittorio of Broglie was also celebrated on 26 February 1816 (Curreli 1997, p. 20). While in Pisa, Mme De Staël frequented two of the salons that just a few years later were to host the Shelleys, Sophie Caudeiron Vaccà Berlinghieri’s and Elena Amati Mastiani Brunacci’s, and she found the latter “plus agréable que toutes celles de Florence” (Addobbati 2004, p. 78).

During her residence in Pisa, Mary Shelley also frequented the home of an English lady, Emily Charlotte Ogilvie Beauclerk, who had come to spend the winter 1821-22 in the city with her seven daughters. Her salon was the only private one in Pisa where dance parties were also held, and Mary went there along with Edward John Trelawny, who escorted her in place of her husband, who abhorred salons, as we learn from the letter he wrote to Thomas Love Peacock: “I find saloons & compliments too great bores; though I am of an extremely social disposition” (P. B. Shelley, 1964, p. 184). Mary Shelley’s journal also records two visits to the Casino dei Nobili, which took place on 11 and 23 July 1821, when the Shelleys were staying at the Baths of San Giuliano. Percy and Mary had also been regulars at the Casino of Bagni di Lucca, where they went every Sunday, though, as their journals and letters show, neither Mary nor Claire Clairmont, her stepmother’s daughter, danced (P. B. Shelley 1964, p. 22; M. Shelley 1987, pp. 217, 219, and 221). This, however, according to what Mary wrote to Maria Gisborne, was simply because they knew no one there: “I do not much like the Casino, since there are no persons that we know there; it would otherwise be pleasant enough. […] I ought to tell you that no English go to the Casino; partly because the festa di ballo is always on a Sunday” (M. Shelley 1980, pp. 75-76).

The Vaccà Berlinghieri and the Mastiani Brunacci salons were likewise attended by Giacomo Leopardi during his stay in Pisa, from 9 November 1827 to 9 June 1828. It was Leopardi who, in a letter to Giovan Pietro Vieusseux, gave Sophie Caudeiron the praising nickname “the beautiful Vaccà” (Viesseux 2001, p. 528), and in 1830 the woman (whose second husband, Andrea, had died in September 1826), participated in the collection of signatures organised by the poet’s Florentine friends for a new edition of the Canti, and also promoted some initiatives to support the undertaking (Del Vivo 2009, pp. 183-84). In January 1828, Leopardi was introduced to the Vaccà Berlinghieri household by the Pisan scholar Giovanni Rosini, while it was Lauretta Cipriani Parra (who in years to come was to become active in the Italian Risorgimento and start a romantic liaison with the patriot Giovanni Montanelli that would lead to marriage) who accompanied the poet to Elena Mastiani Brunacci’s salon. Countess Elena was anxious to meet Leopardi: she nourished a deep interest in literature, and in her youth, she had attended the "Polentofagi Academy", whose name derived from the custom of eating chestnut flour polenta during their literary meetings, which took place in Via Tavoleria, at the home of the doctor and scholar Francesco Masi. Above Masi’s front door, there was a coat of arms in stone representing a table with a pile of polenta on it. In Pisa, Leopardi enrolled in the “Alfea Colony” of the “Academy of Arcadia” under the name of Soristo Delfico and entered the “Academy of Lunatics” choosing for himself the highly ironic name of Giraffe. The latter academy had been refounded in that same year by the Shelleys’ friend Margaret King Moore, alias Mrs Mason, who hosted the meetings in the home where she had recently moved, in Via San Lorenzo (Ceragioli 1997, pp. 321-26, and Curreli 1997, pp. 105-120).

Works Cited

Addobbati, Andrea, “La contessa Mastiani Brunacci e il suo salotto”, in L’Università di Napoleone. La riforma del sapere a Pisa, ed. by Romano Paolo Coppini, Alessandro Tosi and Alessandro Volpi, Pisa, Edizioni Plus, 2004, pp. 71-80.

Agostini, Antonio and Alessandro Panajia, eds, Una “privata Conversazione”: l’Accademia Roncioni e Vittorio Alfieri, Pisa, Felici Editore, 2001.

Agostini Antonio and Sergio Scarselli, “L’Ussero: dal Caffè universitario all’Accademia Nazionale di arti, lettere e scienze”, L’Ussero. Rivista di arti, lettere e scienze 11 (gennaio 2024), http://www.usserorivista.it/?p=674 (last accessed 12/122025).

Alfieri, Vittorio, Vita, ed. by Vittore Branca, Milano, Mursia, 1983.

Ceragioli, Fiorenza, ed., Leopardi a Pisa, Milano, Electa, 1997.

Curreli, Mario, Una certa Signora Mason. Romantici inglesi a Pisa ai tempi di Leopardi, Pisa, Edizioni ETS, 1997.

Curreli, Mario, ed., in L’Ussero: un caffè “universitario” nella vita di Pisa, ed. by Mario Curreli, Pisa, Edizioni ETS , 2000.

De Fecondo Giancarlo and Maria Augusta Morelli Timpanaro, eds, Carlo Goldoni avvocato a Pisa (1744-1748), Bologna, Il Mulino, 2010.

Del Vivo, Caterina, La “Bella Vaccà”, Leopoldo e Andrea. Sophie Caudeiron e i Vaccà Berlinghieri, Pisa, Edizioni ETS, 2009.

Montorzi, Mario, “I Vaccà Berlinghieri: una laica famiglia della borghesia accademica pisana tra scienza, politica e cultura nell’Europa della Restaurazione”, in L’Università di Napoleone. La riforma del sapere a Pisa, ed. by Romano Paolo Coppini, Alessandro Tosi and Alessandro Volpi, Pisa, Edizioni Plus, 2004, pp. 81-91.

Panajia, Alessandro, Il Casino dei Nobili. Famiglie illustri, viaggiatori mondanità a Pisa tra Sette e Ottocento, Pisa, Edizioni ETS, 1996.

Panajia, Alessandro, “Casino dei Nobili. Storia e microstorie”, in Il Casino dei Nobili, ed. by Fabrizio Sainati and Alessandro Panajia, Pisa, Edizioni ETS, 2021, pp. 41-72.

Rossi, Giuseppina, ed., Soggiorni e vicende di Vittorio Alfieri a Pisa (1766-1795), Pisa, Tipografia comunale 1988.

Salvetti, Lucia, Il Casino dei nobili di Pisa nei secoli XVIII e XIX, Pisa, Pacini Editore, 1993.

Shelley, Mary, “Note on the Poems of 1820. By the Editor”, in The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, London, Edward Moxon, 1839.

Shelley, Mary, The Journals of Mary Shelley, vol. 1: 1814-1822, eds Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1987.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe, The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, vol. 2, ed. by F. L. Jones, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1964.

Vaccà Giusti, Laura, Andrea Vaccà e la sua famiglia, Pisa, Francesco Mariotti, 1878.

Vieusseux, Giovan Pietro, Leopardi nel carteggio Vieusseux: opinioni e giudizi dei contemporanei, 1823-1837, vol. 2, ed. by Elisabetta Benucci, Laura Melosi and Daniela Pulci, Firenze, Olschki, 2001.

Nicoletta Caputo, January 2026

All the English translations from Italian are by the author of the present essay

Ultimo aggiornamento

02.01.2026