Viareggio, Percy Bysshe Shelley’s last destination

Commentary

On 8 July 1822, Percy Bysshe Shelley, together with the young boatman Charles Vivian and Edward Ellerker Williams, a retired army officer and friend, set sail from Livorno to get back to Casa Magni, the house the poet had rented in San Terenzo di Lerici. In May 1822, Shelley had commissioned a schooner to be built in Genoa shipyards. This 24-foot and two-masted schooner was named Don Juan as a homage to Lord Byron, although Percy would have preferred to call it Ariel, in reminiscence of Shakespeare’s legendary airy spirit. During the crossing, most probably due to a violent storm, the boat was engulfed by the waves between the Secche della Meloria and the coast of Viareggio. The three men were lost to the sea and their corpses washed ashore in different places of Tuscany’s coastal area.

Williams’s dead body was found on the mouth of river Serchio, in the area of Migliarino Pisano (Grand Duchy of Tuscany) on 17 July, while two days later Vivian’s remains were discovered on the coast of Massa, in the resort of Cinquale, between the ditches of Brugiano and Poveromo (within the confines of the domain of Maria Beatrice d’Este, Duchess of Modena and Massa). On 18 July, the sea gave back Shelley’s body along the shore of Viareggio, a fishing village that had recently developed into a maritime centre with an independent administration thanks to the measures of rehabilitation, economic growth and urban expansion introduced by Maria Luisa of Bourbon, Duchess of Lucca from 1817 to 1824. Strictly speaking, Shelley’s corpse lay on the site of the Due Fosse among the thick vegetation of the Pineta di Ponente, within reach of Paolina Bonaparte’s summer residence “Villa Paolina”, whose construction can be traced back to 1822). The wreck of his schooner was eventually salvaged on 11 September 1822, when two trawlers happened to detect it while catching fish off the coast of Viareggio.

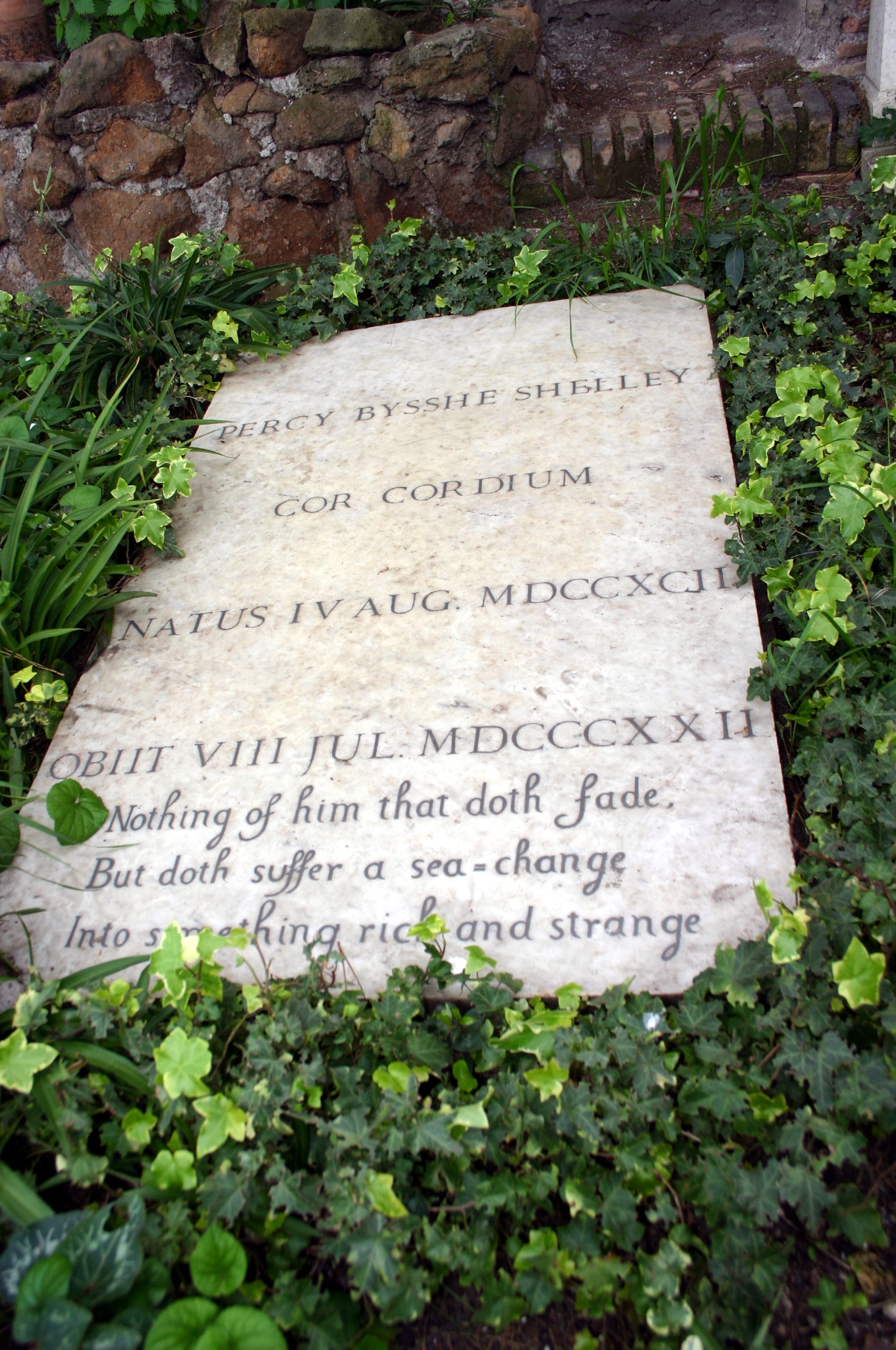

On 18 July, Percy’s badly decomposed body was covered in quicklime and buried on the spot, in compliance with the health regulations and maritime legislation then in force, as attested by the Governor of Viareggio’s letter to the Minister and Secretary of State for Foreign and Internal Affairs of the Duchy of Lucca. The connection between the name Ariel and Shakespeare’s The Tempest, where Prospero conjures up a storm and the airy spirit carries out his command to destroy the King of Naples’s ship, sounded dramatically prophetic, so much so that a memorable passage from Ariel’s Song would be engraved on the poet's tombstone. In like manner, the identification of Percy’s remains was made possible by virtue of a touching detail, namely a copy of John Keats’s Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes and Other Poems, which the authorities found in his jacket pocket. Leigh Hunt had given him this book before Shelley’s departure from the port of Livorno (there is some speculation that the jacket pocket might also have contained a volume of Sophocles’ tragedies). It was Shelley’s dear friend Edward John Trelawny, a privateer, experienced seaman and captain of the Bolivar (Byron’s vessel), who testified to the link between the book and the dead man’s identity. A poet was therefore recognized by way of another poet’s verse and their common fire of inspiration, in an extraordinary synergy that Italy had contributed to enhancing. Tellingly, Shelley’s ashes would be carried to Rome to be interred in the Protestant Cemetery where Keats himself had been buried in 1821, behind the imposing Pyramid of Caius Cestius.

In the summer of 1822, Mary Shelley, Jane Williams, and the other English affiliates who were staying in Italy, such as Byron, Hunt and Trelawny himself, had been doing their utmost to discover what had happened since the day of the sinking of the Don Juan (Mary Shelley to Maria Gisborne). When the tragic news arrived, it dealt an awfully devastating blow, especially to Mary (Mary Shelley to Maria Gisborne and to Clare Clairmont). The English circle decided to have the three bodies exhumed in order to properly mourn and bid farewell to them through a cremation ceremony. The exhumation of Percy’s remains went through various steps.

Thanks to the intermediation of Edward Dawkins, the English Affairs Delegate for the Council of Lucca, the English Legation was allowed to cremate Percy’s remains on the sandy shore where the corpse had been discovered, and inter the ashes in a Protestant cemetery. The funeral pyre was prepared on 16 August 1822 by order of Governor Giuseppe Pellegrino Frediani, with the endorsement of Maria Luisa di Borbone and Ascanio Mansi, the Minister and Secretary for Foreign and Internal Affairs. While lighting the pinewood pyre erected on a metal brazier, Trelawny threw frankincense and salt into the furnace and proceeded to spread oil and wine on the body. Besides Trelawny, the funeral service was attended by the maritime authority officials. While Hunt preferred to remain in the carriage of Byron, the latter was so deeply overwhelmed with emotion as to withdraw to the beach and swim out to the Bolivar (Byron to Thomas Moore). About seventy years later, historical memory, iconic transfiguration, and Romantic imagination were to find an outstanding blend in The Funeral of Shelley (1889) by French painter Louis Édouard Fournier. This famous canvas imaginatively immortalizes Hunt, Byron and Mary as attending the service on Viareggio’s beach: overcome with sentiments of affliction and grief, they stand against the ash-grey backdrop of a cold winter day that allegorically replaces the real-life scorching August season.

In August 1822, right after the cremation ceremony, the oak box containing the ashes of the “Englishman”, or “Melancholic Englishman”, as the people in Viareggio used to call Percy, was handed over to Trelawny to be transported to the Non-Catholic Cemetery in Livorno. However, the British associate collaborating with Trelawny eventually sent the box to one of his correspondents in Rome. After several months, the cremated remains of the poet were deposited in a coffin and buried in the Non-Catholic Cemetery of the Testaccio neighbourhood in Rome. This was a venue that Percy and Mary held dear, being the final resting place of their three-year-old son William, who was struck down by a severe infection in 1819. Percy’s funeral was held on 21 January 1823, but in April of the same year Trelawny ordered the digging up of his remains to relocate them in one of the oldest areas of the cemetery, not too far from Keats’s grave. His intention was to erect a memorial stone and duly pay homage to his beloved friend.

It is well known that, in the following decades, Shelley’s grave grew into a pilgrimage destination and that the very name of the author, in the Anglo-american as well as Italian context, became synonymous with a fearless revolutionary spirit embracing the cause of liberty. At the same time, one should be aware that the atmosphere that surrounded his passing away was steeped with tensions and fears. With reference to Viareggio’s social environment in the first half of the nineteenth century, it must be underlined that one of these fears was triggered by the risk of infection, which led to a particularly strict application of health measures. What remained even more impressed in the collective memory was “the Englishman’s funeral pyre”, which sailors, fishermen and other members of the Catholic populace equated with a gruesome pagan ritual, a sacrilegious act that brought misfortune. If the uncommon practice regarding cremation stirred up superstition, taking on sinister overtones was also the assumption of the immortality of the poet’s heart, which Trelawny is said to have snatched intact out of the fire and given to Hunt (later on, Percy’s heart was jealously kept by Mary, to be finally buried with her in Bournemouth). Legend has it that fishermen in Viareggio went so far as to coin the apotropaic phrase “May I be burned like the Englishmen at the du’ fosse!”.

For over a century, the Due Fosse site was enwrapped in the spine-chilling aura of a cursed place infested by evil spirits. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Bertolio Solman and his wife Enedina Castoldi had Villa Enedina built there; their daughter Zely was to be brutally murdered in that house, which was henceforth renamed “The Haunted Villa”. In the middle of the twentieth century, the same plot of land hosted the headquarters of Viareggio’s Fascist Party. In this area, on 18 July 1945 (coinciding with the day Shelley’s body had been found in the previous century), dozens of soldiers and civilians lost their life and more than two hundred people got wounded owing to the sudden explosion of the mines that had been removed from the beach and temporarily stored in the basement of a nearby building. Further outbursts of violence were documented at the dawn of the third millennium. Nowadays, Viareggio’s municipality is working on an upgrading project concerning this area, which they are committed to converting into a natural park.

Documents

• Letter from Giuseppe Pellegrino Frediani, Governor of Viareggio, to Ascanio Mansi, 18 July 1822, Record n. 89 – State Archive, Lucca: Ministry of Foreign Affairs 79, File 381

[The sea] has thrown out a half-decomposed body […] after a preliminary inspection, the body was buried on the shore and covered in quicklime in accordance with our current health and maritime regulations. Although it was not possible to identify the corpse, one might well assume that it was one of the two English young men who were reported to have drowned during the voyage they had started on 8 July, on board a small schooner that set sail from Leghorn towards the Gulf of La Spezia, the other man’s corpse having washed up on the Tuscan coastline.

• Letter from Mary Shelley to Maria Gisborne, 15 August 1822 (in Julian Marshall, The Life and Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, II, pp. 15-16)

This was Monday [8 July 1822], the fatal Monday, but with us it was stormy all day, and we did not at all suppose that they could put to sea. At 12 at night we had a thunderstorm; Tuesday it rained all day […]. On Wednesday the wind was fair from Leghorn, and in the evening several feluccas arrived thence; one brought word that they had sailed on Monday, but we did not believe them. Thursday was another day of fair wind, and when 12 at night came, and we did not see the tall sails of the little boat double the promontory before us, we began to fear, not the truth, but some illness—some disagreeable news for their detention. Jane got so uneasy that she determined to proceed the next day to Leghorn in a boat, to see what was the matter. Friday came, and with it a heavy sea and bad wind. Jane, however, resolved to be rowed to Leghorn (since no boat could sail), and busied herself in preparations. I wished her to wait for letters, since Friday was letter day. She would not; but the sea detained her; the swell rose so that no boat could venture out. At 12 at noon our letters came; there was one from Hunt to Shelley; it said, “Pray write to tell us how you got home, for they say that you had bad weather after you sailed Monday, and we are anxious.” The paper fell from me. I trembled all over. Jane read it. “Then it is all over,” she said. “No, my dear Jane,” I cried, “it is not all over, but this suspense is dreadful. Come with me, we will go to Leghorn; we will post to be swift, and learn our fate.” We crossed to Lerici, despair in our hearts; they raised our spirits there by telling us that no accident had been heard of, and that it must have been known, etc., but still our fear was great, and without resting we posted to Pisa.

• Lettera from Mary Shelley to Maria Gisborne, 15 August 1822 (in Julian Marshall, The Life and Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, II, p. 19)

On Thursday, 18th, Trelawny left us to go to Leghorn, to see what was doing or what could be done. On Friday I was very ill; but as evening came on, I said to Jane, “If anything had been found on the coast, Trelawny would have returned to let us know. He has not returned, so I hope.” About 7 o’clock P.M. he did return; all was over, all was quiet now; they had been found washed on shore. Well, all this was to be endured.

• Letter from Mary Shelley to Clare [Claire Clairmont], 15 September 1822 (in Julian Marshall, The Life and Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, II, p. 30)

MY DEAR CLARE – I do not wonder that you were and are melancholy, or that the excess of that feeling should oppress you. Great God! what have we gone through, what variety of care and misery, all close now in blackest night. And I, am I not melancholy? here in this busy hateful Genoa, where nothing speaks to me of him, except the sea, which is his murderer. Well, I shall have his books and manuscripts, and in those I shall live, and from the study of these I do expect some instants of content. In solitude my imagination and ever-moving thoughts may afford me some seconds of exaltation that may render me both happier here and more worthy of him hereafter.

• Letter from Lord Byron to Thomas Moore, 27 August 1822 (in Thomas Moore, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron, II, p. 609)

The other day at Viareggio I thought proper to swim off to my schooner (the Bolivar) in the offing, and thence to shore again—about three miles, or better in all. As it was at midday, under a broiling sun, the consequence has been a feverish attack, and my whole skin’s coming off, after going through the process of one large continuous blister, raised by the sun and sea together. I have suffered much pain; not being able to lie on my back, or even side; for my shoulders and arms were equally St. Bartholomewed. But it is over,—and I have got a new skin, and am as glossy as a snake in its new suit.

We have been burning the bodies of Shelley and Williams on the sea-shore, to render them fit for removal and regular interment. You can have no idea what an extraordinary effect such a funeral pile has, on a desolate shore, with mountains in the back-ground and the sea before, and the singular appearance the salt and frankincense gave to the flame. All of Shelley was consumed, except his heart, which would not take the flame, and is now preserved in spirits of wine.

Illustrations

Parco di Ponente, Viareggio (Photo by Marco Ponsi)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parco_di_Ponente_di_Viareggio.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Villa_paolina_in_viareggio_01.JPG

P. B. Shelley’s Gravestone, Non-Catholic Cemetery, Rome

Louis Édouard Fournier, The Funeral of Shelley, 1889, Walker Art Gallery of Liverpool

Bibliography

Belgrano, Fabio, “La ‘maledizione’ di Shelley: il lotto sfortunato di Viareggio”, 9 June 2022, loSchermo.it, https://www.loschermo.it/la-maledizione-di-shelley-il-lotto-sfortunato-di-viareggio/ (last accessed 12/02/2025).

Biagi, Guido, Gli ultimi giorni di P.B. Shelley, con nuovi documenti, disegni di V. Corcos e A. Formilli, Florence, G. Civelli, 1892; subsequently Gli ultimi giorni di Percy Bysshe Shelley con nuovi documenti, Florence, Editrice “La Voce”, 1922.

Curreli, Mario (ed.), Grandi soggiorni: Paradise of Exiles: Catalogo della mostra di stampe, ritratti, manoscritti, cimeli e documenti rari e inediti sul soggiorno di Shelley e Byron a Pisa, Pisa, Pacini, 1985.

Curreli, Mario, “Il mito bugiardo del Golfo dei Poeti”, Godwin Club Italia, 2 (4), 1998, p. 7.

Curreli, Mario, “Golfo dei Poeti, lapidi bugiarde e altri miti”, Soglie. Rivista Quadrimestrale di Poesia e Critica Letteraria, 6 (2), 2004, pp. 19-44.

Fallacara, Luigi, Spiaggia di Shelley e altre inedite, edited by Fabio Flego, Viareggio, Pezzini, 2002.

Flego, Fabio, “‘Straccato’ sulla spiaggia: Percy Bysshe Shelley a Viareggio”, Anglistica Pisana, 12 (1-2), 2015, pp. 25-33.

Marshall, Julian, The Life and Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, London, Richard Bentley & Son, 1889, Vol. II.

Migliorini, Anna Vittoria Bertuccelli, “Le ceneri di Shelley”, in Simona Beccone, Paolo Bugliani, Angelo Chiantelli, and Riccardo Roni (eds), Percy Bysshe Shelley in contesto. Tra filosofia, storia e letteratura, Pisa, ETS, 2023, pp. 35-49.

Moore, Thomas, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron, London, John Murray, 1830, Vol. II.

Pocci, Franco, “La nascita del mito”, in Simona Beccone, Paolo Bugliani, Angelo Chiantelli, and Riccardo Roni (eds), Percy Bysshe Shelley in contesto. Tra filosofia, storia e letteratura, Pisa, ETS, 2023, pp. 99-106.

Pocci, Marco, Il naufragio del Don Juan di Shelley. Cronologia e nautica, Viareggio, Pezzini, 2022.

Trelawny, Edward John, Gli ultimi giorni di Shelley e Byron, Italian transl. Marcella Majnoni and Giuseppe Lucchesini, Roma, Quodlibet, 2025 (ed. or. Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron, 1858).

Viani, Lorenzo, “Memorie minime su Shelley: All’insegna di Prometeo”, Corriere della Sera, 12 August 1930.

Viani, Lorenzo, “Fantasie di vagabondi: Il poeta e il tosacani”, Corriere della Sera, 15 October 1934.

______________

Record by

Laura Giovannelli

Department of Philology, Literature and Linguistics

University of Pisa

(March 2025)

Unless otherwise specified, the English translations are by the author of the present record

Ultimo aggiornamento

18.09.2025